Introduction

When designing Shadow, we wanted to keep syntax as familiar as possible to ease the learning curve. On the other hand, we thought we could do some things more cleanly or more safely. The features below describe some of the syntax that gives Shadow its distinctive flavor.

Sequences

Let’s say you want to assign two different values to two different variables on the same line. To do so in Shadow, you could use a sequence.

(x, y) = (3.5, 6.8);Sequences are syntactic structures only, not types. Unlike Python, you cannot declare a variable with a sequence type. In a sequence assignment, values on the right are copied element-by-element into the variables on the left.

Doesn’t seem all that useful yet? What about for a swap?

(x, y) = (y, x);All values on the right side are evaluated before the assignments. Sequence assignments can also be done with a single value on the right side, storing that value into each element of the sequence on the left. Doing so is called a splat.

(x, y, z) = 0.0; // All three are now 0.0Splats are useful because assignment doesn’t evaluate to a value in Shadow. For example, the following is a syntax error.

x = y = z = 0.0; // Illegal in Shadow!Why did we make that illegal? First, especially with complicated assignments, the results can become unclear in C++ or Java.

// C++ code

int i = 4;

i = i++; // Different versions of gcc get different results for i!Of course, this issue is minimized because i++ isn’t legal in Shadow either. (Use i += 1 instead.) The second reason is the use of assignments in conditions, which is sometimes slick and sometimes an error.

// Java code

boolean value = false;

if( value = true ) { // Always true, but illegal in Shadow

...

}Returning multiple values

Have you ever wanted to write a method that returns multiple things? Of course you have! C gets around the problem by passing pointers. C++ gets around the problem with pass-by-reference parameters. Similarly, C# has reference and output parameters. Java has no good solution, forcing hacks like returning an object created just for the occasion or passing in small arrays to simulate pass-by-reference.

Shadow uses the same sequence syntax to return multiple values and to store them into variables after the return. The following is a toy method that returns both the quotient and the remainder of a division.

public divide(int a, int b) => (int, int)

{

int quotient = a / b;

int remainder = a % b;

return (quotient, remainder);

}Note the slightly different method syntax that puts all return types on the right side of the method header. A method that returns nothing leaves those parentheses empty. Presto! The void keyword is no longer needed. Calling the method behaves the same as any sequence assignment.

(result, modulus) = divide(7, 3); // stores 2 and 1, respectivelyIf you don’t need to store one of the values, just leave it out of the list.

(result, ) = divide(7, 3); // only stores 2var type

Shadow is a strongly typed language, but the types for variables are generally obvious. Java often forces you to spell out the name of a type twice.

// Java code

Crate<Hamdinger, Underwear> crate = new Crate<Hamdinger, Underwear>();Like C# (and similar to the auto keyword in C++11), Shadow provides a var keyword that can be used to declare local variables that have an initializer.

// Shadow equivalent

var crate = Crate<Hamdinger, Underwear>:create();Cat operator

In Java and C#, the plus (+) operator is used to concatenate other types onto string values. Because the plus operator is used for numerical operations, its use can be ambiguous.

// Java code

String song1 = "Love Potion Number " + 4 + 5;

String song2 = "Love Potion Number " + (4 + 5);Since Java concatenation has the same precedence as normal addition, song1 contains "Love Potion Number 45" while song2 contains "Love Potion Number 9". Our solution was to use the octothorpe (#), now commonly called the pound sign, number sign, or hash tag, as a string concatenation operator. This operator, called cat in Shadow jargon, has a lower precedence than addition.

// Shadow code

String song1 = "Love Potion Number " # 4 + 5;In this Shadow version, song1 contains "Love Potion Number 9". There is also a unary version of cat, which is equivalent to calling the toString() method on any object.

Bottle bottle = sea.washUp();

String message = #bottle;Properties

In Shadow, all member variables are private. That’s great for upholding OOP principles, but doesn’t it get tedious writing accessors and mutators for all of those member variables? It could, but Shadow will create them for you at the drop of a hat. Let’s look at a toy Wombat class.

class Wombat

{

get String name;

set double weight;

get set int age;

public create(String name, double weight)

{

this:name = name;

this:weight = weight;

age = 0;

}

}Because the name member is marked get, its value can be retrieved with a property. Properties are accessed with the arrow operator (->).

Wombat bob = Wombat:create("Bob", 12.5);

String greeting = "Hey, " # bob->name # "!";Since weight is marked set, the arrow operator can be used in the same way to store a value into it.

bob->weight = 14.8; // Bob gained weightEven more conveniently, a member that is marked both get and set can be both retrieved and stored, even at the same time.

bob->age += 1; // Bob had a birthday!Of course, properties are more flexible than that. If you want to do something other than the default operations of retrieving and storing, you can write your own.

class Wombat

{

get String name;

set double weight;

get set int age;

public create(String name, double weight)

{

this:name = name;

this:weight = weight;

age = 0;

}

public set age(int value) => ()

{

if( value >= 0 )

age = value;

}

}This second version of the Wombat class has a custom specification for the set part of the age property which prevents users from storing a negative value into age. Note that the name of the method is exactly the same as the member. This method and indeed all properties can also be called directly as methods (since that’s what they are, under the covers), but we suggest that property syntax is used whenever possible.

C# also has properties, but we think Shadow improves on them in a few ways:

- The addition of only the

getandsetmodifiers adds default properties with no extra work. - Properties and their related member variables have the same name.

- Using the arrow (

->) distinguishes a property call (which can potentially execute arbitrarily complex code) from a member access.

Singletons

There is no static keyword in Shadow, but in other languages it is occasionally necessary to use a static member to share a single item among many pieces of code. Perhaps the best reason to do so is the singleton design pattern, in which there is only ever a single object of a given class. Our solution is singleton classes, of which there can only be a single object at any time, per thread.

A singleton object never needs to be created, since its creation is handled in the first method where it appears. A good example of a singleton is the Console class used for command line I/O. Although not necessary, a singleton variable can be used, which is just a convenient alias for the singleton.

Console out; // No create needed (or possible)

out.printLine("Bring rap justice!");

Console screen; // Still the same object

screen.printLine("Shut 'em down!");Immutable classes and references

As most Java programmers know, the String class is immutable, meaning that the contents of a String object cannot be changed after the object is initialized. Unfortunately, the only way to know this is by reading the documentation for the class. In Java, there is no way to declare a class as immutable or enforce its immutability with the compiler.

In Shadow, there is a way. The immutable keyword allows a class to be marked immutable. Any code outside of its constructor that seeks to modify its contents will not compile.

It is also possible to declare a reference with the immutable keyword. In this case, there are no mutable references to the object the immutable reference points to. It can be freely shared between all methods and threads with no concern that its contents will be changed.

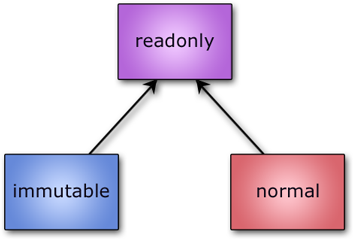

The trouble is that an immutable reference cannot be stored into a normal reference without losing the guarantee that its contents are protected. To mediate between the two different kinds of references, readonly references are used. A readonly reference cannot have any mutable methods called on it. You can store either an immutable reference or a normal reference into a readonly reference.

At first, immutable references seem indistinguishable from readonly references. Remember this: With a readonly reference, someone might have a normal reference they can use to change the contents of the object. With an immutable reference, it’s as if all the references to the object are readonly. No one can ever change the contents of such an object.

Finally, a method can be marked readonly, meaning that it’s guaranteed not to change the contents of the object it’s in. This is similar to const methods in C++. All the methods in an immutable class are readonly automatically.

Deep copying

What happens when you want to make a copy of an object? You can store the object into another reference, but that only creates an alias for the same object, not a copy.

All objects in Java have a clone() method, which allocates a new object and copies over all of its members. Unfortunately, its operation depends on everyone implementing the clone() method correctly for every class. Many developers do not implement the clone() at all. Likewise, the clone() method often cannot perform a true deep copy, in which all the members of the object are also copied. The risk in doing so would be the presence of a circular reference, which would begin a cycle of copying that would never finish.

In Shadow, there are two keywords specifically designed for deep copies: copy and freeze. When copy is used to copy an object, it performs a full deep copy, making deep copies of all the members as well. Internally, the copy command keeps track of all the new objects allocated. If a circular reference would cause something to be copied a second time, the copy command instead uses the first copy. The exception to the rule is immutable objects, which cannot be changed anyway. References to such objects are assigned directly, without making copies of the underlying objects.

The freeze command works exactly like the copy command except that all of the copies it creates are immutable. The freeze command is the only way to create an immutable version of an existing object whose class is not already immutable.

Person stanleyBurrell = Person:create("Stanley Kirk Burrell");

Person mcHammer = copy(stanleyBurrell);

mcHammer.setName("MC Hammer"); // Doesn't affect stanleyBurrell

immutable Person cantTouchThis = freeze(mcHammer); // Can never have its internals changedUseful == operator

In Java, the == operator compares two values to see if they are the same. This comparison is meaningful for primitive types, but for reference types, it only returns true when the two references are pointing at the same location. The proper way to compare two objects in Java is to use the equals() method.

Ultimately, this design causes confusion, particularly since it’s legal to compare two objects with ==, even if it’s rarely useful. In Shadow, the == operator is only valid between an object that implements the CanEqual interface for the other object. In other words, the == operator is syntactic sugar for the equal() method (which does not end with an ‘s’ in Shadow).

For primitive types, the == operator works exactly as you would expect. For object types, the first either has an equal() method defined to work with the second or the code will fail to compile. For reference comparison, the === operator (yes, three equal signs) is available. Fortunately, there are few situations when it’s needed.

(Limited) operator overloading

In effect, the discussion above demonstrates a kind of operator overloading for the == operator; however, operator overloading is a slippery slope. In our opinion, C++ went overboard, allowing even fundamental operators like assignment (=) to be overloaded in arbitrary ways.

The Shadow approach is limited and based on interfaces. For overloading arithmetic operators, the interfaces CanAdd<T>, CanSubtract<T>, CanMultiply<T>, CanDivide<T>, and CanModulus<T> can be implemented to allow overloading of the +, -, *, /, and % operators, respectively. Below is an example of a Complex class for manipulating complex numbers that overloads +, -, and *.

immutable class Complex

is CanAdd<Complex>

and CanSubtract<Complex>

and CanMultiply<Complex>

and CanEqual<Complex>

{

get int real;

get int imaginary;

public create(int real, int imaginary)

{

this:real = real;

this:imaginary = imaginary;

}

public add(Complex other) => (Complex)

{

return Complex:create(real + other:real, imaginary + other:imaginary);

}

public subtract(Complex other) => (Complex)

{

return Complex:create(real - other:real, imaginary - other:imaginary);

}

public multiply(Complex other) => (Complex)

{

return Complex:create(real * other:real - imaginary * other:imaginary,

real * other:imaginary + imaginary * other:real);

}

public equal(Complex other) => (boolean)

{

return real == other:real and imaginary == other:imaginary;

}

}Thus, objects of type Complex could be added together as shown below.

Complex a = Complex:create(1, 3);

Complex b = Complex:create(-5, 2);

Complex c = a + b;In addition to the standard arithmetic operators, there’s an interface for the bitwise operators &, |, ^, <<, >>, <<<, >>>, and ~, but they come as a bundle. It’s expected that they will only be useful for classes that have bitwise behavior similar to an integer, like BigInteger.

Having the CanIndex<V,K> interface overloads the index operator ([]) to read values from an index. Consider the following code that allows array-like indexing of an ArrayList.

var band = ArrayList<String>:create();

band.add("John");

band.add("Paul");

band.add("George");

band.add("Ringo");

String drummer = band[3];There’s also a CanIndexStore<V,K> interface that allows the index operator ([]) to be overloaded so that it can store values into an index. Both interfaces can be implemented independently of each other, allowed classes that can load from an index, classes that can store to an index, and classes that can do both. Consider the following code that stores values into a HashMap using array-like indexing.

var clan = HashMap<String, String>:create();

clan["Russell Jones"] = "ODB";

clan["Clifford Smith"] = "Method Man";

clan["Dennis Coles"] = "Ghostface Killah";Null handling

In C++, dereferencing a null pointer can have unpredictable consequences but often leads to a segmentation fault. In Java, dereferencing a null reference causes a NullPointerException to be thrown. Furthermore, the JVM has to make checks to guarantee that a reference is not null.

The Shadow solution is that normal references can never be null, since most references never need to be: They are initialized to some non-null value or easily could be. In Shadow, only references marked nullable can be null. In order to dereference them or store them into a regular reference, the normal approach is to use the check keyword inside of a try block with a matching recover block. If the reference is null, execution will jump to the recover block. If the reference is null and isn’t in a try with a recover block, an UnexpectedNullException will be thrown.

nullable Hypothesis unknown = getHypothesis();

try

{

Hypothesis hypothesis = check(unknown);

hypothesis.test();

}

recover

{

Console.printLine("It's the null hypothesis!");

}It seems annoying to deal with these nullable references, but they don’t come up very often. When they do come up, the code you write reminds you of the cost of checking them. Alternatively, you can use the coalesce operator (??) to quickly use a non-null value as a default if the object under consideration is null. In the following code, "random junk" will be stored in notNull only if whoKnows is null.

nullable String whoKnows = getStuff();

String notNull = whoKnows ?? "random junk";Unsigned types

All integral Java types are signed. Java added some indirect support for unsigned manipulations in Java 8, but they still don’t have unsigned primitives. We do! Each integral type has an unsigned version. Be warned: You shouldn’t be using these unless you really have a good reason. Shadow type-checking is pretty strict, and unsigned types are not exempt. If you want to store an int value into a uint or vice-versa, you’ll have to do a cast.

See the section on numeric types and literals for details about using unsigned types.

Numeric types and literals

Many languages assume that integer-like types are of primitive type int. In Shadow, even literals are marked with their type, including a u for unsigned values. Below is a table of all the numeric types with sizes, value ranges, and example literal syntax.

UTF-8 support

When C was invented, not many people were thinking about how to store characters from all over the world in computer memory. Strings in C are built on sequences of the single byte char type. Various implementations of C++ have various styles of wide-character support.

Java’s solution was simple and elegant: Use UTF-16. The char type is two bytes, and a String is a sequence of those. Unfortunately, that means that the memory cost of storing plain old ASCII text doubled when compared to C. And there is a hole in the elegance of their solution. UTF-16 sometimes needs two char values to represent some characters, usually from Asian languages.

Shadow’s solution goes a step further with UTF-8, a variable byte size scheme. If you’re using plain old ASCII, it only costs you a byte per character. Many characters can be expressed in two bytes, although some require three or even four bytes. How does that work in a String?

A String is a sequence of byte values. If you index into a location using brackets ([]) or by calling the index() method, you’ll get a byte value. That’s great if all you care about is ASCII.

However, we use the four-byte code (short for codepoint) type to represent arbitrary UTF-8 characters. A String iterator can cycle through a String, returning each code value contained within it.